The Party of Pleasure

Introduction

Sheridan, Louisa H. “The Party of Pleasure.” The Comic Offering, or Ladies’ Melange of Literary Mirth 2 (1832): 325-55. Print.

The Victorian era was a time in British history in which women lived by strict convention, or faced social consequences. Published at the very beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign, Louisa H. Sheridan’s The Comic Offering, or Ladies’ Melange of Literary Mirth, collected various short stories, poems, and cartoons that would have been appealing to women at the time. “The Party of Pleasure” is a humorous account by Sheridan that highlights the social expectations for upper-middle class women of the day, but gently mocks them as well.

The story is narrated by a young woman who, though of marriageable age, is still unmarried, and on vacation with her mother and sister. Because her mother insists on following social norms even while on vacation among strangers, she is forced to visit another family on vacation, the Fraughtons, who invite the women on a picnic. The remainder of the story details the excursion’s follies: windless hours on the ocean, a muddy shore by which one man “loses” a shoe, a picnic upon an anthill with food that did not travel well, a screaming baby, and plenty of young ladies acting ridiculous as they harass a milk maid, several cows, and donkeys. The narration cuts off sharply near the end with ellipses, only to be restarted to issue a hasty conclusion: a few short lines about the narrator’s marriage to a clergyman who had also endured the picnic.

Published in 1832, “The Party of Pleasure” hit the market just nineteen years after Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and probably appealed to many of the same readers. Both stories feature independent, sassy young women who are not afraid to buck convention. Austen and Sheridan both employ a delicate sarcasm in describing the sillier points of life in the mid-nineteenth century. Making social calls, taking long walks in the outdoors, and vacations at “watering-places” were standard luxuries for British women of a certain class, yet both show that these activities are not, at times, all that luxurious. Because the real women of the day could relate to the situations presented in stories like Austen’s and “The Party of Pleasure,” they found humor in the absurd, yet lifelike, representations.

These humorous representations of British feminine life in the early-mid-nineteenth century are what made The Comic Offering successful. Many of the other stories in the journal are funny, like “The Party of Pleasure,” because they could make readers laugh at Victorian life, even the more serious aspects. “The Party of Pleasure” ends most happily in a marriage, which was a hallmark occasion for every young woman at the time. In contrast, “The Spinster’s Last Hope,” also published in Volume 2, is the narrative of a more mature woman who was unable, on many different occasions, to procure a husband. Marriage was a serious issue in Victorian England, and light, fictional accounts both of its successes and failures connected with many women.

Louisa H. Sheridan had a knack for putting together volumes that would appeal to many women at the time. She, as the editor of The Comic Offering, and the author of “The Party of Pleasure,” as well as several other short stories and poems within The Comic Offering, knew what was funny on many different levels. She published pieces that laughed at societal norms, were full of witty puns, and still had good Victorian morals. Yet, despite her prolific writing, little is known about her.

Transcription

The Party of Pleasure

(See PDF Version)

Well! Summer brings with it a thousand agrémens:[1] long bright mornings, dry warm days, moonlight walks, beautiful flowers, delicious fruits: but to the unhappy idle, does it not bring pic-nics?—those attempts at the north-west passage to pleasure, in the discovery of which they are always topped at Repulse-bay by the ice-bergs of ennui and disappointment!

The grey days of Autumn are always welcome to me; because they lead to the period when we commence our social reading, drawing, music, &c.; and also they are the signal for the termination of those dreadful delights, those horribly pleasant pic-nics! I trust the following sketch of one of these overwhelming amusements, may prove that I am more a grumbler par necessité, than a grumbler par métier.[2]

Last summer, Mamma took my sister Charlotte and myself to a watering-place, which was really very pretty; and I should have been delighted with the country-walks and sea-side rambles, if Mamma would have consented to remain unknown for a week or two. To this, however, she would not consent, saying there was nothing so shocking as to see a set of people (females especially) wandering about unknown at a watering-place, as if they belonged to the canaille,[3] whose only chance of happiness rests in their being unknown.

Accordingly she sent her different letters of introductions; and, on the day after our arrival, the ponderous knocks of our acquaintance at the door, seemed to astonish the weak nerves of our brick tenement, which shook and trembled in an ague of fear at every fresh arrival.

This said brick tenement of ours was called “Phœbus cottage,” because the “golden eye of day” poured its rays on one side or the other, from the rising unto the going-down: it was tall and narrow like a canister taken from a tea-caddy, and the winding stairs smelt of the tarred rope which did hand-rail duty: large tables filled up small rooms, and every little corner and nook was filled with shells, plaster figures with faded artificial wreaths, specimens of coral and sea-weed, dumpy tea-pots, stray tea-cups, faded lavender baskets, and every other sort of abomination. I need not describe the red, green, and yellow carpets and tea-trays, the orange bell-ropes, nor the dinner-service, patched up from twenty different patterns:— it is quite enough to say, that we took a cottage merely from the advertisement, without seeing it previously!

It is truly edifying to see the miserable houses in which the most extra-exquisite persons are happy to place themselves for the bathing season: how a delicate lady, who faints in town at an open door, can endure without comment the currents of air blowing from all sides at once of the ill-contrived boxes perches on the edge of a cliff: the most asthmatic, who talk, at home, of being conveyed up and down stairs by machinery, can here ascend these crazy, high, winding flights without hesitation: and those who complain incessantly of heat in their own superb, lofty rooms, appear totally unconscious of it in these small low ovens, exposed to the sun’s blaze all day, without a tree to shade them, and smelling of fresh paints, with the addition sometimes of a coal-tarred paling.[4]

Our visiters were like all other sea-side people; the gentlemen burnt to every shade, from yellow and red, to black, by the sun; some wearing, for coolness, extraordinary hats, and others extraordinary coats, which after all, kept them as warm as the usual kinds: the ladies were mostly disguised in unbecoming deep cottage bonnets, with green and brown veils, strong sand-excluding boots, and silk-dresses of those colours which are “warranted not to change from the sun or salt-water.”

I was rather disposed to like a Lady Fraughton, with four fat daughters, who called upon us; for when I enumerated some of my favourite operas and new publications, they all cordially agreed with me, which gave me a most favorable idea of their good taste! Alas! I soon had cause to alter my opinion of them, for Lady Fraughton said “I hope you are all fond of pic-nic parties, as my girls delight in them so much that we have one almost every day.”

Mamma politely said something vastly in favour of them, and Lady Fraughton exclaimed, “Then you will do us the favor of joining one of our little excursions to-morrow; indeed, my daughters begged of me this morning to invite you, but of course, my dear Madam, I would not do so until I had first ascertained that your demoiselles are as fond of these parties as my own girls.”

My dear Mamma is extremely fond of going out, and Charlottle being too amiable and frenchified to object to anything liked by others, it was agreed that the following morning we should assemble by eleven o’clock, at Lady Fraughton’s, where she promised we should meet none but the most delightfully amusing people in the world; she added, “When a pic-nic party is mal-assorti, it destroys a great deal of the pleasure, you know.”

“Ce n’est pas possible,” said I, sotto voce,[5] to a very fine young man, a college friend of my brother’s, “bien ou mal assorti,"[6] there is no pleasure to destroy.”

The man had the assurance to say, there was often a great deal of pleasure at a pic-nic, and even argued to prove that this depended greatly on ourselves. As I rather like those who occasionally differ from me “in a civil way,” I entered into a long discussion with him on this subject, and we finally agreed to suspend hostilities, until after the next day’s party could be added to the arguments of one or the other side.

As Sir Walter says, “the morning of the day appointed was as fine as if no party of pleasure were intended;” not a friendly shower would come to “dissolve our meeting,” so the party assembled in amazingly high spirits at Lady Fraughton’s Gothic cottage, which was flanked by little round-towers, about two feet in diameter, and surmounted by battlements, from the opening of which frowned cannons of the terrific size of broomsticks: what else could this be named but ‘Castle Cottage.’

The first point to be settled was, “which way should we go?” The Miss Conroys who had delicate complexions which they did not wish to have sunburnt in a boat, said they thought inland views, from a carriage preferable to the monotonous appearance of the water: this was echoed by two clumsy girls, who (although they considered a dusty street full of officers the only pleasant view in the world) did not wish to display Nature’s bounty about their ankles, while jumping in and out of the boats. Mrs. Philip Fraughton, a young wife who thought of nothing but her ‘first-born’ (a baby about six weeks old), fancied that a boat was most like a cradle, or rocking-chair, and of course, seeking an excuse as far from the truth as possible, said there was nothing she enjoyed so much as a seaview: in this she was joined by her fresh-coloured, foolish-looking husband. Charlotte most amiably said that either way would be agreeable to her; I voted for the boats, because I was fearful, by land we should travel (to use a military term) like “seven subaltern’s wives in a post-chaise!"[7] whereas, by water, I might stand a chance of conversing with my handsome opponent; and, I fear I must confess that I intended he should be very much captivated by me ere our return to Castle-cottage. Our hostess and her fat daughters having the casting votes, all declared in favour of the water, and in a large boat we went.

As soon as we were comfortably splashed by the oars, and all those who had a mutual dislike, or coolness, were conveniently placed next to each other, while by changing about to ‘trim the boat,’ all friends were separated, — we found there was a dead calm, and our poor old boatmen labored away to very little purpose for nearly three hours.

A calm at sea has something particularly dispiriting about it: the sea is grey, the sky is grey, the coast is grey: from some effect of the heavy atmosphere on my nerves, the sound of the oars seems twice as loud as usual, and I am always seized with a longing to get away, just when I happen to be in this most helpless and unalterable of situations. The spirits of our whole party were soon exhausted, from their determination to laugh a great deal, when first we set out: whenever a small spark of gaiety did rise from the dying embers of our conversation, Mrs. Philip Fraughton would uncover her baby’s face for a moment, and tell her husband that her “cherub was in a sweet sleep:” a hint which effectually silenced us for some time.

All things must have an end: and at length the rowing match terminated by our landing in some slippery mud. Charlotte and I discovered that we had red and yellow maps all over our dresses, from the awkwardness of a long twig of Scotch nobility, who sat between us, and who was staying with Lady Fraughton during the holidays. Having nothing to say to either of us (as we had not been at the same school with him), he kicked about this huge feet, until he found a resting-place for one in a currant-pie, while with the other he upset a dish of dressed salad.[8]

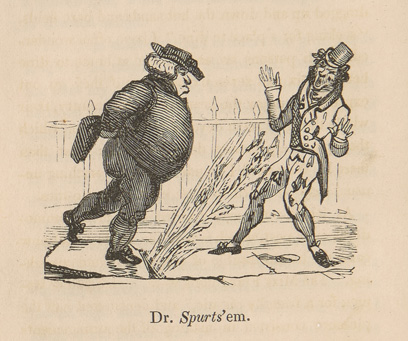

The great wide-mouthed creature too must needs laugh at the effects of his clumsiness; but in striding after my sister to offer his arm, a stone on which he stood turned with him, and he sunk in a bed of Eau-du-Nil[9] coloured mud, from which he rescued himself with the loss of one of his crabshell-shoes. In trying to recover this, he lost the other; and there he stood floundering about in stockings, evidently the produce of some notable aunt’s knitting-needles, veritable, everlasting, homespun, never-to-be-worn-out grey worsted, in the dog-days! Having dutifully looked round to ascertain that Mamma was landed high and dry (and out of hearing too) I laughed aux eclats,[10] and pretending to pull out one of the shoes, in reality pushed it in deeper. On looking towards the boat, I perceived that all my manœuvres where closely watched by the young clergyman, and his undisguised look of disapprobation, proved to me, that any further attempt at charming him would be a complete “waste of powder!” In fact he was evidently displeased that I followed the suggestions of gall against this clumsy disciple of Spurts’em![11]

Instead of looking for pretty views and rural cottages, as some sort of compensation for the monotonous prospect of sullen water, to which our eyes had been accustomed for some time, we were dragged up and down the hot sands and bare fields, “seeking for a place to dine.” I have often wondered, when persons are accustomed at home to dine between six and seven o’clock, that if they go out expressly to enjoy the beauties of the country, their whole thoughts seem devoted to their dinner, which they positively cannot defer to a later hour than three! Why need I wonder? Since everything unusual may be traced to these intolerable pic-nics.

At length our party decided on a most commodious ants’ nest, which was in the shade: and now came the horrid trouble of preparation and unpacking. The Miss Fraughtons were “nice young women for a friendly pic-nic,” and considered half the pleasure consisted in making all the arrangements without the aid of the servants: they insisted on enlisting every one of the guests, and my poor sister, although much fatigued with walking in the sun, went about after these busy girls, with a look of mild resignation, which was enough to make any one angry with her, for her too great politeness.

As for me, I never could understand why being exposed to the sun, and breaking one’s back by stooping to place dishes, plates &c., on the ground, could make the office of laying out the dinner at all more suitable to ladies, than when they might have a table and other means to boot: I therefore made my escape, by very civilly offering to “hold the baby.”

After all, I did not gain much by exchanging one misery for another: a soft mummy-like bundle of shawls was placed across my arms, and I begged so hard to have a little breathing-room given to it, that the young mother uncovered the top of its nose; then as soon as she turned away, I took the liberty of exposing its variegated little face altogether, a process which made it squint at the sun in a most enchanting manner, and frightened me dreadfully, lest its little goggling gooseberry eyes would never look straight again!

I had never before held such a young, helpless, little jelly in my arms, and I was terrified, lest its head should fall off, or at least twist round, until the back part came before: so, I sat motionless, watching all the alarming grins, and strange colours, which passed over its odd little countenance, and also the pugilistic positions into which it screwed up its parboiled, odd-looking hands. Every person who passed within two yards of me, was greeted by the young parents, with “Mind the baby,” and they came so frequently to me, requesting me to change my position,—to raise one arm, lower the other, turn on different sides for the sun, or the shade, or the breeze, — in fact, they disturbed my little charge so completely by their over-care, that it became cross, and cried most lustily.

Here was a horrid event! Mr. and Mrs. Philip Fraughton, had just lifted a huge hamper of plates between them (these married lovers always hunted in couples); but when the shrill cry reached them, from my poor little burden, they let fall the hamper, flew across the nearly-arranged dinner, upsetting the mustard, and the only jar of water which was brought.

The young mamma, in tears, vainly tried to lull the cries of her baby; but these young things do not much like to listen to reason, and they are little machines more easily set going than stopped: so, during the rest of the day, she sat away from us, with her husband beside her, vowing, they could not be so inhuman as to eat until baby had ceased crying: —baby ceased not, so they ate not, all day.

The provision baskets, had all been overset, by some of the party falling, while trying to get out of the boat; so, on being unpacked, it was discovered, that the cream was all over a half-boiled ham, the syrup from a cherry-pie had paid a friendly visit to the pigeons in a pigeon-pie; and a quarter of lamb was covered with the panada[12] of baby-Fraughton. The wine-basket was left in the boat, to be[13] mulled by the sun; the jar of water was upset; and the salt, oh the dear, dear salt! was “clean forgotten.”

Ladybirds, grasshoppers, earwigs, genteel-looking spiders with little waists and long legs, in fact all sorts of creeping things were soon in the midst of every dish on the table: while the ants, “being native burghers"[14], of the place, of course made themselves at home without repast, and ourselves.

Every person appeared to me to be helped to exactly the things which they dislike: poor Charlotte, and the other fat-haters, received most pinguid[15] portions: Mamma, and all the lovers of spices, and cayenne, were doomed to veal, chicken, and other anti-piquant things: while the tedious operation of carving fell to the share of every bashful, hungry, or awkward being at the party, my poor hapless self forming one of the latter uncompassionated class!

No one save the Scotch boy would taste the currant-pie, and the cayenne pepper had fallen into the other tarts. The fruit was shaken into a most inedible mass: the hard apples had bruised the soft figs, the pears had no compassion on the gooseberries, and the peaches had behaved most tyrannically to the raspberries: and, in fact, the whole repast and dessert was so devoid of comfort, that we were all glad, when Lady Fraughton proposed leaving the gentlemen à l’anglaise.[16]

“Then how to pass the time away, Till tea-time, was the doubt: Twas much too hot for sitting still, Twas worse to walk about!”

We threw ourselves on the first green bank we[17] found, and began what was intended for conversation. Alas! ‘twas plainly to be seen, that although these ladies bestowed the most affectionate epithets on each other, while many dear friends sat clasping each other’s hands, or waist, yet they felt not the slightest interest in the passing scene: yawns were smothered, bright eyes closed, and brows contracted — bonnets were tied and untied, parasols opened and shut — exclamations against heat and fatigue became general. In this agreeable mode the eyes of all the group were turned on Charlotte and myself, who were asked to sing; and they stared us out of countenance just as if we were hired for their amusement, and therefore could not be as tired and warm as the others!

Having, however, declined singing, it was next proposed to walk in search of shade, and we toiled up the brow of a sandy hill, which, crumbling at every step, deposited specimens of the soil through our bas à jour;[18] and, having strayed through sundry lanes, barns, and mud-edifices, at length we found ourselves in a large field where a girl was milking.

This sight completely enlivened most of our young ladies; and as it was pronounced to be ‘quite delightful to drink warm milk!’ they ran across the field, screaming and giggling, and soon surrounded the stupid short-haired girl, who did not seem much rejoiced to see them. In answer to their vociferous demands, as to how they should manage to obtain a drink, she unwillingly produced a small rusty tin can, into which she sulkily poured some of the frothy delicacy for each of the party in turn, who drank it in the most rural manner possible, all full of hairs, grass-seeds, and insects. A view of the milk-maid’s hands quite satisfied mamma and her “twa bairns”[19] without tasting this rustic treat; but our refusal called forth many sly shrugs, sneers, and confidential whispers of “affected things!” “How I hate finery at a pic-nic!” &c. &c.

Being now tolerably satisfied as to the flavor of warm milk, our rural fashionables next wished to try the process of procuring it from the cow; and, amidst screams of laughter, one of the Miss Fraughtons sat down on the three-legged stool, trying, but without success, the power of her thick short fingers.

The second sister, reproaching Miss Dorothea for such stupidity, desired us all to look how well she could manage to play milk-maid; and accordingly she ran to a large, wild-looking, brindled cow with twisted horns, whose small sly eyes had been frequently turned towards us, shewing the whites of them with what equestrians term a “stirrup-look.”

She was, perhaps, incommoded by the pressure of Miss Fraughton’s hundred and fifty rings, — or no sooner did she feel that young lady’s grasp, than she kicked the tin can violently, sent the fair milkmaid rolling on the grass (who screamed ‘à l’Irlandaise’[20] that she was killed!), and finally came up towards the rest of the party in a heavy trot, which gradually increased in speed, tossing her head as she uttered a deep, hollow, prolonged “Moo-oo-oo,” like thunder.

She might have approached us merely from a wish to ascertain whether we allowed her little calf to slumber quietly, and stretch its knotted limbs lifelessly in the sun: we did not, however, wait to study Mrs. Brindle’s maternal anxiety, but scampered away in full cry, stumbling and jostling in the greatest confusion and terror, thus, of course, inducing the cow to follow us.

I had reckoned confidently on being enabled, by my often-tried speed, to outstrip the others, reach the farm-house, and send men from thence to the relief of our party: but, as I was bounding past fat Lady Fraughton, she seized me so suddenly as almost to throw me down on my face, at the same time gasping out —

“You run the — quickest, I see — dear, so — you shall stay — and help — me on — or I shall —be killed — Oh!”

I had nearly sunk under her weight in the morning, as she leaned on me while getting out of the boat; but in the afternoon, terror had either added to her weight or diminished my strength, for I really found her immoveable, and we were soon passed by even the tortoises of our group, while I heard “Mo-oo-oo” gaining quickly upon us.

My companion, in despair, now turned round to ascertain how near death was to us, and, not perceiving a deep drain we had approached, she fell into it, dragging me after her with her grasp of terror! — I never heard any human voices sound so melodiously as those of the farmer and his boys, who jumped over the hedge and frightened away the enemy: it was even delightful to hear him scold us for “worreting the beastis”[21] as he angrily expressed it.

When I rose, Lady Fraughton, instead of apologizing for pulling me down, began upbraiding me with having hurt her when I fell! The disagreeable, unreasonable old thing! I could scarcely help wishing to knead her deeper into the drain and leave her there. However, on finding she was really hurt, I assisted her with much care to the bank we had named as the general rendezvous. Here, reclining under a tree, and sketching, we found one of the our party, namely, my adversary, the young clergyman, to whom Lady Fraughton related (with many expressions of gratitude) “the great kindness of the dear girl who would not desert a feeble old woman;” and although I scarcely merited her encomiums, I was delighted to find my handsome opponent not only had relaxed from his late stiff manner, but he really betrayed so much interest in the story and every thing else which concerned me, that I began to think another discharge of the captivation artillery would not this time be ‘powder wasted.’

In about an hour afterwards, the other ladies began to drop in, two and two, like chesnuts from their husks; and such a catalogue of pleasures as they gave us! Two had slipped into a stream, while gathering brook-lime, which they mistook for water-cress; and after eating a great quantity, they recollected that it did not taste like the latter plant, therefore they concluded it must be poison. Two dear friends had seen some hens with chickens, and, wishing to fondle some of the little yellow downy things, had taken them away in spite of their anxious mothers; these, finding remonstrances had no effect on the fair robbers, flew at them, and pecked the frightened damsels until they dropped the ‘callow brood.’ Two more had been seized by the watch-dogs of the farm-yard while chasing the ducks, and only escaped in consequence of their flimsy dresses, which fortunately tore, and set them free, although they left more than half their gowns in possessions of their wondering canine foes, who had never before attacked any thing less tenacious than fustian[22] or linsey-woolsey: while, in the same unlucky farm-yard, another pair had “hunted sweet little pigs, and had a famous play with them,” as they said, until the mamma-pig attacked them on one side, while on the other the old farmer threatened to “teak the lawr on um for pleaguin’ the young things, and botherin’ on um so.” The last pair who arrived, had sauntered sentimentally up a green lane behind the farm-garden, and encountered three donkies with little foals frisking beside them. The young ladies wishing for a ride, seized upon a long-eared mother and child; and while one was quickly upset and kicked by the matron-steed, the other girl (the fattest of the fat Fraughtons) threw down the weak infant charger who was about two months old: this astonished the friends exceedingly, for they could not think why a little donkey should not stand at least as well as an old one.

The animals, however, taking a dislike to the intruders, began to collect round them, putting back their long ears, and puckering up their lips ready for a bit; so the frightened friends were obliged to scramble over the garden-fence to effect an escape, and, while looking round to ascertain that the donkies did not follow them, they overturned some bee-hives which they had mistaken for strawheaps; the choleric little inhabitants, whose anger they had thus excited, soon took ample revenge for the unintentional offence, and really the poor girls were in a dreadful and pitiable state from the venomous stings. After half an hour spent in condoling with the sufferers, Lady Fraughton found it was useless to expect our John Bulls[23] to leave their wine, and we returned to wait for them in the boats, where at length they arrived, sunburnt, grass-stained, flushed, stupid and yawning.

The same provoking calm had continued all day, lengthening our long voyage; nothing was heard but anxious wishes for a breeze, or any change from the dull calm; and the clouds becoming weary of our complaints, gathered themselves into a dusky mass, and poured an angry shower over the repiners, to prove how much worse their fate might be. The poor baby cried, and its helpless mother went into hysterics. Lady Fraughton, who hated her with the true mother-in-law feeling, was delighted at an opportunity for uttering sneering and disagreeable things: this the young husband angrily resented: —although a slave himself to his tyrannical mother, he did not choose to have his poor little wife scolded, having taken her away from a happy home. As she happened to be younger, prettier, more accomplished, and more admired than the Misses Fraughton, they never forgave such deadly sins: and they agreed (in one instance during their lives) with their mamma in persecuting their new relation, whom they annoyed with truly feminine talent, protesting to every body that they were vainly striving to please Emily, who was evidently prejudiced against them! The present was a golden opportunity for these young ladies to rail against weak nerves, expressing a hope that they had been formed without any! “Very likely,” returned the angry young man, “for I have always heard that any thing without nerves has no feeling!” This rejoinder enraged his female opponents most terribly, as they had no answer ready, a most provoking situation for those who pride themselves on making bitter speeches: so they all took refuge in dignified silence, while we, the poor hapless guests, were afraid to lift up our eyes or our voices.

My young clerical friend looked perfectly horrified at this disgraceful exhibition of feminine unamiability: I could not help watching the changing expressions of his face; the last chilly frown settled on his brow, according to my interpretation, clearly indicating a firm resolution to avoid the whole deceitful sex: so my artillery was actually wasted after all! I believe he was a convert to my opinion relative to pic-nics, as I never heard of his joining another all the time he remained at the seaside. As for the others * * *

How abruptly I left off my story! But I have not time to finish the history of other people, because (being just married to this same young clergyman) we are on the point of going abroad. Strange to say, we have changed opinions about the pic-nic parties: mon mari[24] says Lady Fraughton’s was the most disagreeable odious attempt at amusement he ever knew, and that all my attractiveness was requisite to induce him to remain! Now, since I have heard this last confession of his, my gratified vanity gently whispers, that it really was not such a bad pic-nic as I at first imagined!

Notes

- ↑ French: “Agreeable qualities, circumstances, etc.” OED

- ↑ French: “By business.” (Google Translate, Google, Web, 7 November 2014.)

- ↑ “A contemptuous name given to the populace; the ‘vile herd’, vile populace; the rabble, the mob.” OED

- ↑ “A fence made from wooden pales or (later also) metal stakes.” OED

- ↑ Italian: “In a subdued or low voice.” OED

- ↑ French: "Well or ill-assorted.” (Google Translate, Google, Web, 12 November 2014.)

- ↑ Likely to mean travel in an overcrowded fashion.

- ↑ The original reads “sallad,” an older form of the same word. OED

- ↑ French: “Nile water” (Google Translate, Google, Web, 7 November 2014.)

- ↑ French: “Burst out laughing.” (Interglot Translation Dictionary, Interglot.com, Web, 12 November 2014.)

- ↑

- ↑ “A dish consisting of bread boiled to a pulp in water.” OED

- ↑ The original reads: “b”

- ↑ citizens OED

- ↑ “Of the nature of or resembling fat, fatty; greasy, oily” OED

- ↑ French: “In an English style or manner” OED

- ↑ The original reads: “w”

- ↑ French: “open-worked stocking.” (Technological Dictionary in the English, German & French Languages:.. Ed. Alexandre Tolhausen, Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1878, Google Books, Web, 12 November 2014.)

- ↑ Scottish: children.

- ↑ French: “the Irish” (Google Translate, Google, Web, 7 November 2014.)

- ↑ In the original, “worreting” could also be read as “worreling,” though either way the meaning is unclear.

- ↑ “a kind of coarse cloth made of cotton and flax,” or “a thick, twilled, cotton cloth with a short pile or nap” OED

- ↑ “typical Englishmen” OED

- ↑ French: “My husband” (Google Translate, Google, Web, 7 November 2014.)

Edited by: Youngberg, Erika: section1, Fall 2014

From: Volume 2 (The Comic Offering, or Ladies’ Melange of Literary Mirth)